100 ways to make music

What are the essential skills we need to help pre-school children enjoy and make music? Engaging with children is an art, just like parenting, and as such there is no simple prescribed method. Each moment, each situation, calls for flexibility, empathy, humanity and open awareness, as well as knowledge derived from previous experiences.

The founder of Reggio Emilia wrote a poem about children having a hundred languages, a hundred ways of thinking, of playing, of speaking (see the full text: www.chevychasereggio.com/poem.htm). Working on Redcliffe Children’s Centre’s current Youth Music project in central Bristol I’m reminded of this, as I see that there are a hundred ways of supporting children’s musical explorations.

Everyone a musician

The project is entitled ‘Everyone a Musician’, and a year into the project I’m still absorbing the empowering message in that title – I am not the musician teaching non-musicians, I am amusician, encouraging other musicians. Music is not something that I do and you learn, it’s something we do together.

Our culture defines a very small percentage of people as ‘musical’ and leaves the majority thinking they can’t sing or contribute musically. Yet many cultures have no concept of being tone deaf, with music made by the whole community at celebrations and ceremonies. We make music when we speak - language is inherently and intrinsically musical, our voices rising and falling and placing rhythmic emphasis on different words and syllables. And our ears hear this music in speech, and read the emotions being expressed – kindness, tension, aggression or calm. So we all use our voices musically every day of our lives.

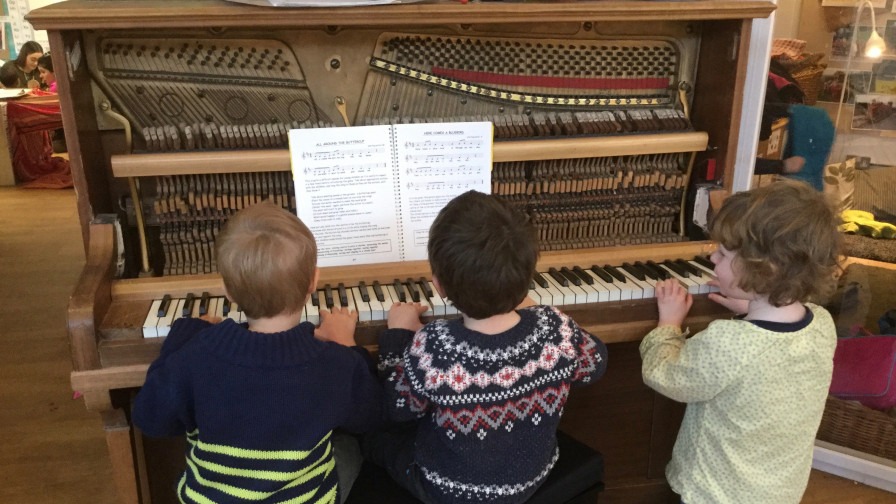

The children are musicians – they know that, they’re not old enough yet to have taken on the idea that most people ‘are not musicians’. The staff are musicians – they actually already have all the skills and technical knowledge necessary to encourage children in their music making. The parents are musicians – well capable of enjoying music with their children just like anything else they share together.

In keeping with current early years practice, some of the most important work in this project involves observing, labelling and encouraging musical behaviours that are already there. The practitioners and parents often don’t know they are musicians, so it’s important to see and celebrate their musicality.

Sara: communication above technique

The word ‘communication’ comes from the same root as ‘communion’, and in its literal translation from Latin means ‘building together’. Likewise music making is about being in the moment making sound together.

Observing staff member Sara has taught me that this communication is more important than what we think of as musical technique. She is willing to sing a song with enthusiasm with the children, strumming a ukulele with no greater skill than them, but feeding off their energy, responding with her voice and her body, moving, raising her voice, strumming louder and quieter, faster and slower. The group have a great time, the children feel encouraged to use their voices more, dance in time with the song, make suggestions, create their own words, put great emotion into the music.

This is high-yield practice, with children enthused, energised and developing new skills and confidence. Reflecting on it, I see that Sara is using many skills here – to be uninhibited, to sing and use instruments, to listen, engage, respond, move, change tempo and dynamics, but perhaps above all, to let go and enjoy – and not think about ‘not being musical’. This is very different from the conventional parameters of musical technique, such as vocal tone production, singing in tune, knowledge of chords or melody on an instrument, or the ability to talk about music.

In some ways Sara is in a better position as a ‘non-musician’ to be open to new possibilities. My skills and experiences tend to narrow my views about what constitutes musicality and how I can encourage it. My mind is full of crotchets, melodies, chords, terminologies, old songs, concepts of how instruments should sound, and comparisons with other experiences. But it’s only when I observe with an open mind that I see the myriad ways that people demonstrate musicality.

You play, I copy

Every childcare practitioner and parent can confidently join in with children’s movement or playdough activity. Translating this into musical context, likewise we all have the skills necessary to do this in relation to children’s musical explorations – ifwe can put aside the notion that we can’t. I use the acronym MIRROR – Match, Imitate, Respect, Reflect, Observe, Repeat – to label this simple technique which is the most appropriate form of music lesson for pre-school children.

Once again, this doesn’t need sophisticated technique in the traditional sense, but does require empathy and interest in what children are doing. We need to be able to copy the speed and volume of children’s playing, the quality and pitch of their voices, and match their enthusiasm. And to remember that music doesn’t require instruments – it may be vocalising in play, or tapping with found objects.

Doing this we are joining children in the here and now. So much of what is familiar to us is new to them. One of my favourite musical recommendations is to tear a piece of paper very slowly, close to your ear. We have no previous experience of this, unlike when we see an instrument and instantly bring to mind memories of how it sounds. We can listen unencumbered and afresh. It’s like how we spend much of our time listening to the chatter in our minds and not experiencing what’s around us. All the things that have already happened, or we want to happen, or fear may happen, or that we need to do, these all take us away from hearing, seeing, feeling, smelling and being in the moment. Can we be in this moment, with this child?

Up-joying with ukuleles

Projects like this often talk about up-skilling the staff. When those new skills enable them to enjoy music more, potentially transforming their working experience, the term up-joying seems more appropriate. We have half a dozen staff members developing their ukulele playing. Some know one or two chords, some have neat folders of songs with chords and seek out new ones themselves on the internet, some ask how to play particular songs.

All the staff took part in a ukulele session at the Inset day at the start of the project, and we’ve had staff ukulele times, and parent ukulele times. More recently I feed them new songs and chords on an ad hoc basis. One of the unforeseen benefits is that staff are often modelling learning for the children. When children see adults in the act of learning, outside their comfort zone, struggling to absorb new information, there’s a new commonality which supports the children’s all-round learning.

Musical encounters

We are bringing a wide range of musical groups into the nursery to perform and engage with the children and families. So far we’ve had a wind quintet, a ukulele orchestra, a jazz duo, and a trip-hop duo using loops, with forthcoming events including a string quartet and African drummers.

The children have got used to these live performances and don’t need to be invited to join in: as well as dancing, they may uninhibitedly playing drums or blow recorders along with the adult players blowing saxophone. We hadn't foreseen this, but it makes sense that young children would see live music as an invitation to join in.

Aother form of musical encounter is the headphone jukebox where several children at once can listen autonomously to a wide variety of recorded music on mp3 players.

‘I’m not a musician but….’

This was how a parent began telling me the story of the song he’s made up and sings with his two-year-old at bedtime every night. He and his daughter have great fun together through making up, singing and varying their own personal song. What could be more empowering?

The exploration and reflective practice continues. There are times when it seems nothing new or interesting is happening, then suddenly something emerges which couldn’t have happened in structured, led sessions. Staff members sing with more confidence, and use instrument much more. Parents have donated instruments, and others come in to play their instruments. One practitioner uses recorded music to get children dancing animatedly. Another has picked up on children’s interest in movement and shown them clips of modern dance, particularly by male dancers, which her group have been very interested in. Large sheets of paper and pens are available next to musical instruments, and some children re-present their musical exploration in picture form. A PGCE student says how much more confident she is with music than a few months ago, and a new volunteer who didn’t know about the project commented that music seems to be as important as any other aspect of learning in the centre. Parents report wonderful things happening at home, and staff are finding new enjoyment.

Commonalities

On the one hand, I continue to grapple with the indefinability of what the creative and musical process is, and to marvel at seeing new things going on that I haven’t thought of. On the other hand, I think it’s useful to ponder what is common to the different approaches people are taking to supporting children’s music making.

The first thing I see is a genuine interest in what the children are doing, an ability to form a strong connection with them, and an enjoyment of whatever the musical activity is. This is the most important ingredient, the human connection, in the same way that research into successful therapy has shown that the relationship is more important to the healing than what method the therapist uses.

Secondly, there is a willingness to have a go, not to be held back by the concept of not being a musician. This may mean being flamboyant like Sara is, or using quieter instruments in keeping with our calmer personality. It may mean spending time learning a new song or a few chords on a ukulele. It will very likely mean stepping outside of our comfort zone of familiarity.

Thirdly, we use our ability to listen, to use ears and eyes, heart and mind, to respond to children’s musicality. We listen to the main ‘three dimensions’ of music - volume, pitch and speed, but also pay attention to the type of sound and the emotion being expressed. With practice we develop and refine our abilities and gain confidence.

Finally, there is a willingness to experiment, to not see music in isolation, but connected with other learning, with movement, with mark-making, with creativity and vitality in general. Whether it’s a song for bedtime, a spontaneous dance, or an old favourite song played around with to make it new. Music doesn’t fit into a box, any more than people do.

"Music is the space between the notes. It is something to be felt. Although it does not have a concrete and precise definition….all of us know that music is every sound that reaches our ears and our heart says that it is something fabulous.....that is music." –Claude Debussy

Bill Roberts will be at the MERYC-England Conference in Bristol on November 9th-10th this autumn, where he will present a workshop 'Riding the Musical Moment', and a practice paper 'Connecting music and emotional development'. For conference information and bookings visit http://www.meryc.co.uk. (MERYC is Music Educators and Researchers of Young Children and leads the way in music practice).