3. Group activities for spotting musical potential

If you can spend time working with or observing individual children, it can be easier to identify their potential. But how do you do it in a group environment? Working with Hugh Nankievill and others, Awards for Young Musicians developed a set of group music-making activities, alongside filming and observation, that can be used to identify individual musical potential.

Suggested exercises

The vast majority of footage across this resource shows Hugh Nankivell employing a series of materials/exercises with young people which he found to be most effective in identifying facets of musical potential across participants within the group.

Hugh writes: ‘By a combination of good judgement, experience and luck the musical approaches and materials we decided to use when we began to develop the film resource strand of this programme (in the summer of 2010) worked as effective tools in identifying individuals demonstrating facets of musical potential in a group. We were therefore able to produce a clear series of connected film-clips and contextual writing.

‘In the summer of 2011 we were asked by AYM and the other programme partners to extend this research to work with a number of other groups of young people in both formal and informal music settings. We essentially used the same musical materials for these sessions and again were able to identify individuals and make a set of films along with accompanying writing. The music leading approach taken was largely traffic light in nature which resulted in us being able to spot individual facets of potential with relative ease.’

Some of materials that Hugh developed and utilised later on in the process proved to be less effective (see Problematic Exercises for his explanation). However here’s an outline of what Hugh feels to be the key characteristics of the exercises that can effectively enable music leaders to identify facets of musical potential in group work.

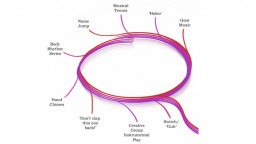

The characteristics of this work are:

- It’s directed by an experienced music-leader who clearly leads most of the exercises, largely taking the traffic light approach.

- The material is creative in nature, requiring the participants to invent their own elements and contribute them to the whole.

- The material is primarily not repertoire-based, although all groups did sing a traditional song, Holeo, during their sessions.

We believe that these characteristics are key to explaining why the workshops involving this material are successful in identifying facets of potential within young people in a group.

(When teaching repertoire pieces there is usually considered to be a right way and a wrong way, or at least a way that is better than another way. So if a full class are all being taught to play the same rhythm on the drum or the keyboard (for instance) it is often easier to spot those who are getting it wrong rather than those who are positively exhibiting musical potential.)

The major category into which this effective material falls could be defined as ‘creative rhythmic play’ and is directed through initially using body rhythms and then moving on to percussion work. There is also some use of call-and response song

1) Creative Rhythmic Play

1a) Body Rhythms

This series of exercises consisted of Hugh beginning, and then repeating, a simple body rhythm (clapping/stamping/slapping etc usually in 4/4) and then inviting individuals to respond to that initial rhythm by finding their own complementary rhythm to fit with that and listening to, and observing, the whole process.

When a music leader presents a repeated rhythm and asks the group to respond creatively to that rhythm, then differences between participants’ listening, their approach to the sounds they make, their confidence, and their musical choices, and so on, can usually be seen and heard. This means that the ensuing piece of new music is created and composed by the members of the group (they cannot get it ʻwrongʼ as it is their choice as to what they play) and they often respond positively to being the creators as well as the performers.

1b) Creative Group Instrumental Play

The Creative Group Instrumental Play pieces were very similar to the ‘Body Rhythms’ but using instruments instead of body sounds.

For these exercises a collection of mixed percussion was used. This means that when analysing and observing the film it’s very clear to see and hear the different contributions that are being made. A cowbell is a very different sound to a xylophone or a cabassa and, with a group containing these different instruments, the differences of playing and listening and observation can clearly be seen and heard.

When a whole class plays the same instrument (see Problematic Exercises) e.g. all clapping, all playing drum sticks on chairs, all playing keyboard, all playing ukelele etc then it is much more difficult to notice any differences in playing. Of course it is not impossible, but it is much more tricky.

2. Call-and-response songs

Two non-western traditional call-and-response songs were used. These were used as a warm-up and to gauge how the group would respond to vocalising together.

When a repertoire song was used it was interesting to notice the difference between a song where there was an element of creativity for the group (in Holeo for instance where they were asked to invent a body movement to accompany a particular rhythm, and where they had to remember a change that was different from the leader) and one where it was purely listening and copying (Tongo for instance). Tongo was useful because it gets the group singing and generates a positive response as, usually, it results in a really good sound. However, it does not easily lead to identifying any particularly clear musical potential by any individuals.

Goat Music

Some of the groups created an ostinato-based percussive/instrumental/vocal 3-part structure called Goat Music, originally invented by the community band 'Dangerous Volume' from Huddersfield. This was only ever played after we had played some of the Body Rhythm pieces and the Creative Group Instrumental Play and is an extension of those ideas.

For this piece one person starts a percussion (instruments or body sounds) ostinato and the rest of the group join in, one- by-one, with their own ostinati. When everyone is playing percussion someone can change to making a vocal ostinato: this is the cue for everyone to gradually change to singing their own vocal ostinato. When everyone is using their voice this is again the signal for someone to change back to percussion and to play a third ostinato. Again everyone gradually joins in on percussion. Once everyone is playing percussion again, each person drops out one-by-one. (This structure can be modified so that parts 1 and 3 are, for instance, on pitched instruments/voices and part 2 on percussion).

At the end of Goat Music everybody in the group must describe what kind of a ‘Goat’ it was that they have been playing.

Goat Music reveals many facets, in particular (6) inclination to lead – through observing who starts each section and who plays last, (2) active listening – through noting who played solid and confident interdependent rhythms, and (8) expression - by noting the vocal sounds used and the descriptions of goats that are made at the end.

Hand Chimes

I took along a set of Hand Chimes (enough for one per person in the group) and led a number of exercises using them. To begin with I made sure that everybody was comfortable with the chimes and could play them. I then got the group into a circle and, playing one note per person, we tried to play evenly round the circle a few times. We then repeated the exercise but in the other direction.

A third play involved passing the sound to either left or right and using body/eye contact to determine which direction you wanted to send the beat. The aim was to keep the beat going evenly throughout, even though it was constantly changing direction. Finally we played the hand chimes by passing it in any direction, to right and left as well as across the circle to anyone you wanted. With some groups we also explored further approaches with the chimes.

After each play we discussed the activity and made observations. These discussions frequently included tempo, individual responsibility, the sound world and creative ideas.

As with The Name Game and Name Jump I’m aware that it can be easier to spot the people who are having difficulty and making mistakes than to spot those who are playing really well. However, within these hand chimes exercises one useful observation is those who are ‘in the body’ when playing and this can be seen as (3) absorption in the music and, at times, (4) commitment to the process. This aspect of ‘in the body’ can often be clearly seen in Hand Chimes through observing those who tap their feet or move their body as the sound is passed round the circle. Hand Chimes pieces can also indicate (1) enjoyment, (2) active listening, (5) inclination to explore, (6) inclination to lead and (8) expression.

Holeo

Holeo is a call-and-response song, with actions, originally from Ghana and traditionally sung while walking to work in the fields. There are three called lines, A, B and C. In sections A and B (see the score) the response is the same as the call, but for the C section - which is always repeated four times - the response is different. This little change often trips people up. On each occasion I asked the group to find/invent actions for the responses, and accepted the first ones that were offered. It was always sung several times.

Through using Holeo with the elements of individual creativity (suggesting actions) and the use of movement we can potentially observe enjoyment (1), active listening (2), commitment to the process (4), inclination to explore (5), inclination to lead (6) and expression (8). In addition, on returning to the song later (at the end of the session if only leading one, or at the start of the second session) we can observe who has remembered the changes. We can then observe clearly which individuals also have a good memory (7).

Musical Tennis

Musical Tennis was an activity used with some of the groups. Musical Tennis is another musical cueing game, this time involving clapping and clicking.

It is a game for pairs (a duet) with player one serving and player two returning until, on a particular cue, player two becomes the server and player one the returner. The game continues with the service swapping over without losing the beat.

The game is in 4/4 and sounds only ever happen on each of the four beats. If the server claps one beat and clicks the next this is the signal for the returner to fill the bar up with two claps. If the server claps twice and then clicks this is the signal for the returner to fill the bar up with just one click. If the server claps three beats followed by a click (e.g. uses all the beats up in the bar) this is the signal for the returner to become the server. The new server now leads until s/he leads with three claps followed by a click and so on with the serving passing back and forth.

Here is an example – P1 = player 1, P2 = player 2, X= clap, Y= click

P1X P1X P1Y P2X

P1X P1Y P1Y P2X

P1X P1X P1X P1Y

P2X P2Y P1X P1X

P2X P2X P2X P2Y

P1X etc.

When teaching Musical Tennis I explain the basic rules and then ask for a volunteer to try it out with me. Once I have tried it with a couple of players I then get the group into pairs and observe them playing it together. Musical Tennis is quite a complicated game and for that reason I did not play it with all of the groups. In addition, because the last phase (in pairs), becomes ‘roundabout’ leading it becomes much more difficult to observe individuals.

When playing Musical Tennis we can usually observe most of the facets apart from (8) expression and (5) inclination to explore (although of course if the piece develops in ideas and discussions these can also be observed). However, we noticed that (6) inclination to lead and (7) memory can be observed through seeing which participants volunteer to play it as a duet with me, in front of the others. We also observed certain individuals helping others (leading) when in pairs, through body movement and other subtle conducting approaches.

Name Game and Name Jump

We began every session with The Name Game and primarily used it as an introduction to learn people’s names (and so we had an audible record on tape to identify everyone by name) and also to check whether the whole group had a shared understanding of a repeated rhythm and a comprehending of a musical instruction.

The Name Game. A simple clapped rhythm is given by the leader (crotchet, quaver, crotchet, followed by a crotchet rest) and in the first rest someone says their name (as a solo) and in the next bar’s rest the whole group says that person’s name, and so on around the circle, alternating between solo and chorus until everyone in the group has said their name.

We then went on to develop this into Name Jump. Sometimes we would lead straight on from The Name Game to Name Jump and on other occasions would do the extension Name Jump at the second session.

For Name Jump the same rhythm is used as in The Name Game, but this time in the first rest somebody has to call out the name of another person in the room and in the next gap the person whose name had been called has to call out another person etc. There is no echoing of names in this extension and you cannot predict when your name will be called and therefore need to be ready to respond at any time.

Using these two name games can identify individuals demonstrating most of the facets, (apart from perhaps 6 - inclination to lead - and 8 - expression). But in fact we have not used filmed examples from this because, whilst this exercise is generally useful for a number of reasons (it can be fun, is a good ice-breaker and helps learning names) it’s actually more likely to isolate those who are NOT exhibiting musical competence (e.g. they do not listen and miss their name being called, they find making immediate responses very difficult and so become tongue-tied or they find multi-tasking tricky).

Switch / Guh

With some of the groups we played a musical follow-my-leader game initially known as Switch. To begin with I ask all the class to follow me in the sounds that I’m making (slapping knees, humming, beating chest etc.) and to change whenever I change. I then ask the class to invent a one syllable word that has never been heard before: in one school a child suggested the word ‘Guh.’ This then became the name – and the key word – for the game. I again lead the sounds, but the group only join in when I say the word ‘Guh’ and if I change sound they must not change until I say ‘Guh’ etc. As one girl pointed out ‘it’s a bit like ‘Simon Says.’ After I had led it a few times I invited an individual from the class to lead it.

Switch/Guh is a structure that is known, but where the content is always different: therefore relies on the members of the group to focus at all times on the leader. If the group is confident and generally understands the process then the leader can develop the piece by moving more than one sound ahead of the class before saying ‘Guh.’

With Switch/Guh we can often note which young people are enjoying the process (1), actively listening (through using ears and eyes) (2) commitment to the process (4) and - as the piece develops - memory (7). Also, through noting who wants to lead the group and how they then do so, we can also observe (5), (6) and (8).

Don't Clap This One Back

Don’t Clap This One Back is a call-and-response game with certain musical cues.

To begin with I will clap a rhythm and ask the group to echo it back and continue in tempo with a series of different rhythms, all in 4/4 time. Once I have established if the group can do this I stop them and explain the first ‘cue.’ I clap the rhythm ‘Don’t Clap This One Back’ (long long, short short long - see manuscript) and explain that when they hear this rhythm they should stay silent.

I then play a series of different rhythms with the group echoing each one back, occasionally putting in the ‘Don’t Clap...’ rhythm. I will continue this for a while, usually until the whole group is silent after I play the ‘Don’t Clap This One Back’ rhythm.

If the group as a whole understands the game and is following, I will then introduce another cue (see manuscript for a selection of options) which requires a different response from the group (e.g. slapping knees or stamping feet). Again we play the game and I will mix up a combination of different rhythms to see if they remember the cues.

Next I will ask the group if they can come up with their own musical cue which has a verbal mnemonic. After receiving one or more responses, we try them out, choose one, and play the game again. Finally I ask the group if anyone would like to lead the game with all the different cues.

Playing Don’t Clap This One Back is a good game to identify which people show an inclination to lead (6) and clearly those who can remember musical cues (7 memory). However, it can also be used to identify those who are attentively listening (2) and we have a good example of a young person who is completely committed to the process (4) and can observe her working out a new rhythmic cue to present to the group.

FOOTNOTE

When playing Don’t Clap This One Back I’m interested to see who volunteers ideas and who offers to lead, as this can indicate leadership, expression of creative ideas and strong rhythmical confidence. However from our detailed analysis of the film footage we’ve also discovered just how much some students can be understanding and internalizing the game without ever offering any verbal contributions. The ones who volunteer ideas and themselves as performers are often the ones that will be most easily noticed in any class group (certainly the ones that the regular music leader will most commonly be able to comment on). However others who never lead may also exhibition elements of facets (1), (2), (4) and (7).

Body Rhythm Series

This is a flexible series of body-percussion exercises. I always began with the same starting point and develop it in different ways with different groups. To begin with I start a repeated pattern (an ostinato) in 4/4 time, using body sounds (clapping, tapping, slapping etc) and then I ask the group to join in with me, playing their own invented body-rhythm ostinato which fits with my rhythm. Once the whole group is playing I will shout out ‘when I count to four stop,’ then count to four and see if everyone stops at the same time. This game is called Body Rhythm.

Depending on the overall group ability and amount of time we have I then develop this straightforward starting point, of multiple complementary ostinati, in a number of ways.

I regularly led a piece called Body Rhythm Gap. Once each person has their own ostinato I ask them to remember this as their ‘home rhythm.’ We then play it three times and then rest for a bar. We continue to do this until the group is comfortable with the 3 bars of playing and the one bar of resting. Next I introduce a free solo by each person in turn into that bar of rest. We then go around the circle one-by-one playing a solo in turn in the gap.

I also introduced Body Rhythm Change whereby once we were playing our own ‘home rhythm’ I asked the group to learn somebody else’s ‘home rhythm’ without changing from their own home rhythm. Then on a cue led by me - (e.g. ‘1.2.3.4 - Change’) everyone would change to that rhythm and play it repeatedly until, on cue again, going back to their own ‘home rhythm.’ This developed with different groups, some learning several new rhythms, and always coming back to their original ‘home rhythm’ ostinati. The changes and instructions were called out as the piece progressed rather than stopping and starting each time.

This series of Body Rhythm pieces can relate to most of the facets except perhaps to (6) an inclination to lead. In terms of (2) – active listening – it’s interesting to note that in a series of games like this ‘listening’ often comes through watching as much as through using the ears. This is especially true in Body Rhythm Change, where individuals are learning someone else’s rhythm while ‘keeping their own one going. We also discovered a number of good examples of (5) – inclination to explore – through nothing individuals who found new and interesting ways to create their own body rhythm.

Creative Group Instrumental Play

With each of the groups I led some Creative Group Instrumental Play sessions. These usually came at the end of the session and always came after we made some Body Rhythm pieces and were very closely related, but used percussion instruments instead of body percussion.

Initially I gave out a range of different instruments, one to each person, and asked the group to play them freely for a few minutes to make sure they were comfortable. I always made sure that I had a selection of different instruments that were not technically difficult to play. These always included un-tuned percussion (shakers, wood blocks, claves, small drums, cow-bells, agogo bells, cabassa etc.) and sometimes also included some tuned percussion instruments (glockenspiels and xylophones).

I would then lead a series of ostinato-based games/exercises, usually following a similar pattern to that described in the Body Rhythm pieces. Sometimes I would begin and ask the group to come in whenever they found a rhythm they liked and at other times I would conduct them individually (with a nod for instance) to come in one-by-one with me.

After we had played an ostinato percussion piece I would often invite one person - who I had noticed as playing an interesting or complementary rhythm - to play their rhythm with me in a duet.

Sometimes I would split the group into two and one half would be the audience while the other half played a directed Creative Group Instrumental Play piece. This gave a good opportunity for the audience to identify those individuals who they thought were playing in a particularly interesting way. It also let the music have more space, especially if in a group of over twenty young people. We always had discussions about the music after we finished playing.

I always made sure that instruments were swapped at least once during the session so that everyone got a chance to play more than one instrument.

The Creative Group Instrumental Play pieces relate to most of the facets in almost the same ways as the Body Rhythm pieces but including, this time, examples of (6) an inclination to lead. We have examples of individuals playing a rhythm and helping (leading from within the group) and others who are struggling to cope with the structure, e.g. stopping after 3 bars. Also, as in the Body Rhythm pieces, we have examples of (5) - inclination to explore - as seen in the instruments that certain individuals choose (ones that are unusual or very quiet) and the way that they decide to play the instruments once they’ve selected them.

Using these activities with young people

Materials

None of the material used is technically complicated, but it does need some skill, practice and confidence in order to lead it, especially in terms of keeping one part going while observing the group and calling out instructions.

The material described here is designed to elicit clear individual responses from the group, both musically and - at times - verbally. It can generally be considered ‘traffic light’ teaching/leading. Some of the exercises can lead onto more involved small group work and discussion (‘roundabout’ teaching/leading) but in the exercises we led, we mainly kept the group playing and working all together.

Arrangement of the space

In all of the spaces we visited we rearranged the room, often making it completely different from ‘normal’ group sessions. We made a large clear space in which to play. In most cases we then got the group into a semi-circle (sitting or standing) facing the music leader. (On the occasions when a semi-circle was not possible, we got the group into a circle).

This rearrangement of the furniture and the people in it (e.g. stacking up chairs and tables, getting the group off the stage and onto the dance-floor or turning the group to face into the room instead of facing away sitting at keyboards) was for a number of reasons. The main, practical reason was for:

- identification of individual facets of potential. When observing them (and clearly when filming) we needed to be able to see all of them.

However, there are other reasons for this rearrangement – two in particular:

- for many of the exercises and games everyone in the group needs to be able to see everybody else, and

- to demonstrate that music sessions do not have to be in one particular format (e.g. behind keyboards or on stage) but can easily be changed around.

Try it yourself

One aspect of this project, revealed immediately after the practical sessions, was the way in which several of the group’s regular music-leaders commented to us after being given the opportunity to observe their group without leading it. Several music leaders noticed individuals with a whole range of different musical attributes whom they had never previously observed in this way. They were able to make this useful identification by virtue of standing back and watching their group from the sidelines while the group was led through this particular series of musical activities.

These music-leaders felt that this aspect of the project was, in some cases, the most important as it was a clearly useful aspect of their CPD (continuing professional development).

For this exercise we are suggesting that you - as music-leaders - watch these examples and see if you can identify any individuals who are presenting facets of musical potential. As has been demonstrated by the notes on the facets, we are not expecting that you will necessarily have the same responses that we do, or that ours are the ‘right’ ones. What we are trying to do is persuade you to look at an activity in a slightly different light and to see if you can observe one or more people with musical potential.

Watch each example as many times as you like and notice how much you can observe through repeated watching. Make sure that you focus for some of the time on the people that you might not be expecting to reveal anything and see what happens.

Good luck - and enjoy it!