Exploring the outcomes of Youth Music’s funded programme in 2019-2020 - Long Read

All projects funded by Youth Music are required to use our outcomes approach to help plan and evaluate their activities based on the changes their work brings about. The outcomes approach provides the framework for Youth Music’s application and reporting processes, enabling us to develop a rich dataset for evaluating the impact of our investment. Youth Music funded projects set a few outcomes at the beginning of their project: these can be musical, personal or social outcomes for young people, or workforce and organisational outcomes for the sector.

Once projects come to an end, organisations funded by Youth Music report to us on their progress and present evidence showing the ways in which their project helped them to achieve their intended outcomes. In the financial year 2019-20, Youth Music received 148 final evaluation reports, which were processed and analysed by members of Youth Music’s Grants & Learning and Research & Evaluation teams. All the outcomes and quotes explored in this article are taken from these evaluation reports.

Projects are expected to use Youth Music’s quality framework, Do, Review, Improve, to plan and reflect on their practice. The framework is designed to support music-making sessions that foster personal and social, as well as musical, outcomes. It values young people’s existing musical identities and promotes a creative, young person-centred approach to learning.

Musical outcomes

For many participants of Youth Music projects, this was the first time they had ever taken part in any musical activity.

- A quarter (26%) of core participants had never made music before.

- 47% were new to the organisations delivering music activity.

The majority of evaluation reports detailed some kind of musical outcomes for young people, even if musical outcomes were not the intended ones set at application stage.

For many, this involved an improvement in a musical skill, either in specific instruments/vocal techniques, or writing, performing and music technology.

Musical skills

Participants had built their technical abilities when it came to playing an instrument or singing, either in one-to-one sessions or through learning in a group setting. Projects provided a wide range of information about exactly how participants’ technical abilities had improved, such as learning “chords on the keyboards, guitars and performing in assembly” (5291) to being able to “support their own tuning singing a cappella (…) in 3-part harmony” (5723).

Some girls were able to memorise and perform leaping-ostinato on piano, others were able to learn and perfect their drumming skills in particular. Things that were covered included playing unison rhythms on percussion instruments as part of a large group and playing different instruments as part of a large group, playing with delicate touches in an aleatoric style to complement an improvised dance routine and singing on their own or as part of a large group. In every single case, there were improvements in pulse, timing, pitch and robustness of sound. (6095)

Alongside technical instrumental and vocal skills, projects often reported an improvement in music technology skills. These included learning how to record, mix and produce music, as well as how to set up equipment for recording or performing, DJing, and many other valuable skills relating to the use of specialist equipment and software:

90% of the participants attending had no prior music production or software DAW tuition or skills. At least 98% of the participants attending Increased their skills in the studio. Participants told us they had improved significantly and music leaders and participants reported that they were confident in using computers and a range of software such as Ableton, Logic Pro X and Fruity Loops to produce music for themselves of with others. (6477)

Projects such as the one quoted above often work with young people with little to no formal music education. In many cases, the use of technology in music making projects can be an effective way of engaging young people quickly, as progress in skills and knowledge can be observed relatively quickly, giving newcomers to music making a sense of mastery in a short space of time.

Using technology to make music has been more beneficial than ever this year for many young people who have been unable to make music in their usual ways due to COVID-19 and social distancing restrictions. Youth Music grantholders can now access VIP studios for free, meaning that young people on their projects with an internet connection can access the cloud-based music production software at home. Feedback from current grantholders has shown this partnership to be a beneficial one:

Youth Music's increasing role as sector support advisor, as well as grant-giver, is welcome. The link with Charanga is a good example. This has made our online delivery a lot easier and more accessible to young people. The contact has also opened up a wider productive relationship with Charanga. We parent about VIP Sessions from the Youth Music newsletter and it has significantly assisted our projects during (and after) the Covid-19 crisis (Stakeholder Survey respondent).

Performance and expression

Development in musical understanding – reported by many projects – can lead to improved skills in performing and expressing it to others, and many projects saw an improvement in participants’ musical performance skills. This was sometimes in the form of performing a song or piece of music expressively:

“We used an iPad to allow each young person to play an expressive solo. To follow this, we introduced body percussion, moving onto a set of chime bars ... This progressed further than expected, and turned into a copying game, led by various members of the group.” Level 1 Mentor (5291)

For others, this was about building the belief in their skills to feel comfortable and confident performing to others, and this was often evidenced by positive feedback from audiences made up of other young musicians, music leaders, parents, and members of the wider community:

The large increase of 69% from the self-assessment questionnaires demonstrate that the young people themselves acknowledged a growth in their own musical ability and confidence. This is corroborated by the music leader who observed a gradual building of musical confidence in the core group of young musicians, especially when it came to performing the music in the recording studio. This was also concurred by the youth staff at the three different youth organisations. All noticed what was described as 'magical moments' where the young people, who previously might have not engaged much in the session, suddenly request to perform a song they've been working on and have the confidence to perform it solo. (5948)

Composition/songwriting

The aforementioned understanding and appreciation of how music works can also lead to better-informed songwriting and composition, and many projects reported an increase in this type of skill among participants:

Detainees who were more experienced musicians were able to reconnect with skills through facilitated music activities such as songwriting.

D1: It helped me to rediscover my writing skills… it had been a very long time that I had ever wrote music, that I had ever wrote lyrics, you know, so when we started at first I just used to do freestyles you know, but when they started giving me topics to write to it kind of brought that out back in me, and ever since then I’ve been trying to write just a little bit of bars (6329)

Musical understanding and communication

Alongside projects reporting concrete skills in songwriting and composition, there were also improvements shown in the ability to communicate through music. This was sometimes still linked with songwriting, with participants demonstrating their increased musical skills and confidence through the music and lyrics they were writing:

- 100% expressed improvement in their lyric writing, performance as a result of their studio sessions. (5305)

"What was really good was that she has become quite critical with decisions in music making - said no to something I suggested and suggested something else which was really amazing! It's the first time that’s happened." (5900, project working with Learning Disabled participant)

For participants in other projects, communicating their own personal experiences through original music and lyrics appeared to be a valuable skill and experience, and this also sometimes helped them to reflect on the way they listen to other music:

“We began to write lyrics for our group song which led to a huge outpouring and sharing of some of their emotional experiences surrounding being in care, having a physical health condition, struggling with anxiety and being labelled as having a mental health condition.” (6368)

“The importance of meaning and authenticity emerged from young community participants’ accounts. One young participant emphasised the importance of real-life story-telling when describing the difference between music that is meaningful and music that is not:

“Basically, if you’re writing lyrics or a rap for a song, first of all you’ve got to have a good topic to rap about. Cos if you listen to a song and think that’s a banger, that’s a good song, it’s always got a good meaning to it, like you really believe that what the person’s trying to tell you. But if you listen to a song about painting windows, or watching paint dry or like how you go to the gym and lift weights and shag birds, no-one’s like ‘yeah I totally feel that guy that’s what I do’ … but if someone talks about their struggles and maybe their ups and their downs, or maybe tells a story through it, or has a meaning to do it then that’s where it becomes good I think. Like you really feel their lyrics.” (6329)

On a similar note, many reports discussed the idea of participants’ self-expression being improved. This is particularly important when working with young musicians facing barriers to music making. Many of the young people our funded organisations work with experience situations and circumstances that have a huge impact on their lives, and often it can be difficult to find the right way to express or communicate their feelings. Writing and performing original music offers a different way to express these difficult feelings. Youth Music is currently in the process of researching the idea of self-expression through music and lyric writing further, as it is a topic widely covered in evaluation reports and is thought to improve participants’ emotional wellbeing:

"When R is engaged in music, he is happy, he is able to express himself clearly, he creates compositions using apps or drum rhythms that reflect his mood, his feelings. He has used the djembe to express his frustration often starting with really loud unrecognisable sequences that gradually turn into recognisable patterns, when this happens, his face, his whole body changes from being tightly wound to more relaxed, fluid and softer. Once he has had that release he appears much calmer and regulated and is prepared to listen and engage with others." (6618, Music mentor)

The idea of expressing yourself through music can often be linked with communicating particular thoughts or feelings with others, and this appears to be the case for many participants. However there were also themes in evaluation reports about the other ways participants communicate musically. When playing together in a band or ensemble, musicians often use non-verbal cues to communicate with their fellow musicians. Participants’ non-verbal communication through music improved in several projects, with reports noting how participants listened to each other, kept time, and sang/played with a sense of togetherness.

In the other two schools, students with profound and multiple learning difficulties were largely non-verbal, but demonstrated enhanced communication and team-working skills as the project progressed - getting increasingly involved in using their instruments, listening in order to play together, and expressing support for others' ideas. (6752)

Another frequently occurring theme on the subject of musical understanding was the idea of participants’ improvisation skills improving as the projects progressed, often leading to skills in playing and writing non-improvised music as well. Young musicians’ spontaneous musical contributions became noticeably more sophisticated over time, suggesting an improved understanding of different ways to play and sing music:

Survey measured each child's confidence in singing, leading an activity, clapping a rhythm, improvising an instrument. The 288 baseline surveys completed by teachers, through observation, showed that 26% of the 288 children demonstrated an imaginative response to music in November of 2018. In June of 2019, the final survey completed by teachers showed that 85% of the 288 children demonstrated an imaginative response to music. (6619)

Musical awareness

Alongside the technical and communicative understanding of music shown above, young people (and often, parents of very young children) demonstrated an understanding of the ways in which music can contribute to their life outside the immediate environment of the project they took part in.

There were several mentions of young people being made aware of the variety of different musical opportunities available to them, and for some, this seemed to show the beginnings of shaping musical identities as listeners/audience members as well as performers:

“We hadn’t been to somewhere like The Sage before. It was a very good evening and we liked it. The people performing were young like ourselves so it was good to see what performing live is like." (6358)

In many projects, participants were not only made aware of musical genres that had been previously unknown to them, but were able to experience their own and each other’s musical cultures in new settings:

Every session started with a group discussion about music and concerts they had been to in last week, discussions about style and culture making them more aware and more understanding, it also enable young people to make friends with other young people from different backgrounds. Parents told us their children had made friends with a wide range of people and that they regularly contacted each other outside of the project to collaborate on music or to attend other music events and concerts. […] Young people attended the project from over 23 different countries which led to interesting conversations being held between participants. They learned about different music from each other and they learnt to respect each other’s customs and lifestyles. (6477)

For other projects, participants were made more aware of the many different musical careers and further education pathways available to them such as “promoting and organising events, [and] producing videos” (5302) taking music at GCSE (6358) or going to college to learn about music (5723). There was also a sense that some projects gave participants a sense of the realities of working in the music industry:

At the beginning of [the project] 80% (24) of the 30 young people cited that they had no knowledge of the music industry and that it was 'very hard to get proper advice'. 20% (6) said that they had some knowledge. At the end […] 93% (28) of students said that [the project] had met their needs and improved their knowledge. (6481)

Finally, several projects (particularly those working with Disabled young people and early years) highlighted how participation had broadened the awareness of music’s impact among parents and carers, often resulting in increased confidence in using music and singing at home, outside of the project environment:

“Parents have commented on how their children are singing the songs at home and how nice it is that they can sing along with them.”

And from a parent: “It was a great bonding experience with our own children too, practising the songs together at home. In particular we would sing along to some of the songs on YouTube, with the whole family joining in too.” (5913)

Accreditation

Many of the projects have accreditation offers available for the young people they work with: this is usually approached in a way that is responsive to the progression needs of each individual.

Some projects mentioned that accreditation could be offputting to participants. For example, in one project where participants were referred “mainly due to their lack of focus, concentration and achievement in class” the sessions offered “a place for them to feel that they could achieve something without the barrier of accreditation frameworks” (6618). In another project, young people were seen to be “wary of the term accreditation”. Particularly for those “failing at, or not attending school”, the words “grade/exam [have] in the past acted as a barrier” (6440).

Likewise, for projects working with young people experiencing mental health problems and low self-esteem, accreditation was not always a priority when working with young people “frequently arriving in crisis” (5948). However, many projects were able to overcome these barriers through flexibility, creativity and long-term engagement.

Overall, 8% of core participants (n=3,448) received some sort of accreditation through the programme they attended. The proportion receiving accreditation has decreased from 14% in 2018/19, which is most likely due to variation in the projects reported on in this period. 63% of the accreditations (n=2,157) were Arts Awards:

- 1,158 Arts Award Discover

- 259 Arts Award Explore

- 630 Bronze Arts Award

- 67 Silver Arts Award

- 43 Gold Arts Award

Personal outcomes

Projects reported on a wide variety of personal outcomes for the young people they worked with. These encompassed many intrinsic personal outcomes that influence young people’s overall wellbeing (such as confidence, self-esteem and general life satisfaction) as well as extrinsic developments (such as engaging or re-engaging with education or employment, and learning transferable skills).

Intrinsic outcomes

One of the most commonly-reported personal outcomes for young people was confidence. For many, this was aided by the creative and performance aspects of the projects, leading to a stronger sense of self, and confidence in themselves, which transpired in other areas of their lives too:

One powerful example of this can be found in the case study of a seventeen-year-old trans male who arrived at the start of the project with very low self-esteem and whose voice contributed to his gender dysphoria. He was a keen poet, centring around his life experiences, but unable to sing in front of others due to being so uncomfortable with his own voice. The [project] workers… enabled the young person to edit his poetry and transform it into songs but also used a stepping-stone method to teach him good performance skills. (6083)

For some, self-confidence went a step further: young people said they “felt proud” (6360) or experienced “increased self-worth” (5883), which often came from “feeling useful” (5739) or as if their roles in the project had given them a sense of purpose. This in turn was seen to be “linked to increased motivation and determination around the pursuit of their goals” (5943).

Alongside these deep personal changes to self-esteem, self-worth, purpose and confidence, there was also a huge amount of evidence to suggest that participation in Youth Music projects lead to increased happiness and life satisfaction. Intrinsic personal outcomes such as these are important products of Youth Music funded work at any time. However, in these circumstances, when the mental health and wellbeing of younger people is at a low due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the benefits of music-making are needed now more than ever:

During the termly reflections, the staff discussed wellbeing, guided by the Wellbeing Scale, and there was an absolutely unanimous conclusion that [project] makes everyone feel better - more relaxed, more confident, happy and energised. (5931)

Overall our scale results indicated that [project] has had a positive impact on young people that have taken part and they have greater personal levels of wellbeing and also that the project had made a positive impact on them. (6116)

This sometimes was particularly evident in projects doing targeted work with young people at risk of experiencing mental health difficulties:

D2: … it was an experience to savour, you know what I mean? An experience that’s probably going to stick with me for a very long time, like he said, to stay positive in a place like this is very, very hard, trust me. So yeah, this is gonna be … something I’m gonna tell people about, when I was in there … there was something to look forward to and it helped me pass time like that. It was nice. (6329)

While increased happiness and improved mental health could be attributed to any combination of the types of personal outcomes evidenced above, we should not downplay that one main benefit of taking part in music-making for young people is about simply enjoying themselves and having fun, and is often a good distraction from the other things going on in their lives:

I have a lovely memory of Mila telling me about her music sessions… and singing ‘Havana’. She was so happy when singing. Due to the nature of her illness Mila was often fatigued and understandably frustrated. It is clear how important these music sessions were as they gave Mila time to engage in an activity she enjoyed and provided distraction. (6471)

Extrinsic outcomes

There were many commonly-reported extrinsic personal outcomes relating to skills not directly related to music, as well as engaging (or re-engaging) with education, employment and training. Many young people developed transferable skills as a result of participating in a Youth Music project. These included (but were not limited to) leadership, event management and facilitation skills:

For the first time this year we undertook training of one of our past participants and volunteers to be a peer facilitator. By the end of the year she was helping the lead facilitators/project directors by leading warm-up games at the start of the session. She also played a big part in her voice section taking on a semi-conducting role for choir members who had difficulty with the music in terms of timing and tuning. In her role, which crossed over from being participant to member of staff, she was a useful conduit for choir members to express any issues they were reluctant to share with project directors. Her contribution to the work was invaluable and having her in this role was a great help to the directors. (5723)

The largest development of leadership roles was in the organisation of Void/Evolve as this was both an exhibition/album launch and a gig. This also involved working closely with another organisation, the Star and Shadow who have their own unique way of working as they are run solely by volunteers. This meant that most [project] members had to undergo volunteer training involving fire safety training as well as familiarisation with the environment and systems for filling roles for events. (5739)

The older primary children, both hearing and deaf, enjoyed the opportunity for gaining leadership skills by being Signductors and helping the younger children. (5931)

Other skills built included literacy and numeracy skills, in particular how increased literacy and language skills assisted young people with their communication (6192, 6851). For some young people, participation in a Youth Music project helped them to think about (and in some cases pursue) the different careers available to them. These didn’t always necessarily involve music:

This course has help me a lot [to] gain not only knowledge of the music industry but has given me confidence in myself and in my abilities. It has made me think of my career path in more depth and not just take one path but to meet new people and to take different route. In the future I would love to make my own music one day, but I also love finding new artist and new music so I’ve been looking into one day maybe having my own record label. (6481)

Over 75% of core participants have gained part/full time employment since engaging with [project]. The tutor/mentors have given much needed help and support with CVs, online presence, job applications, university and college applications and course research. (5883)

D3: For me I want to do something like community work and that, personally I see myself as a people’s people, like bringing people together and being involved with that obviously made me think that, you know what, I can do this. So yeah, it really made a big difference. (6329)

Progression

Reports contained a variety of different activities that participants were signposted towards. While many of these were musical activities, others (including those specifically designed to target particular groups of young people) focused on education or employment, with a small number of projects also reporting young people being signposted to other types of art/creativity/leisure, or accessing external services.

The majority of reports focused on how young people had been signposted towards new musical opportunities following the end of the project. Some talked about how participants had progressed on to individual/one-to-one music sessions, however far more commonly, reports discussed participants progressing on to other types of group music making. These were sometimes offered by partner organisations. Other organisations offered multiple projects, allowing participants to progress internally.

Several projects also reported young musicians progressing to making more music in local music scenes. Some talked about how they had enabled young musicians to explore performance opportunities in the area, either as part of their project, or beyond:

The [project] participants were given a stage at Hockley Hustle where they performed tracks created on the project and new work where they had collaborated with others. They were also given the opportunities to play on other Hockley Hustle stages. Many of the participants have been given gigs with I'm Not From London who have been partners in the project. [Project] have been offered a stage at Beat the Streets festival in February. (6877)

Education, employment and training

For many projects working with young people aged 16 and above, progression to employment, education or training was a positive outcome. In 2019/20, in projects where the majority of participants were aged 16 and above, an estimated 23% of participants engaged/re-engaged with employment, education or training as a result of the project.

"I have learnt a lot from doing the research. I didn't realise how many different opportunities and types of courses were available to me. It is definitely good to know what things are out there as I now know, from the interviews, that a lot of work in the arts can come from word of mouth and putting yourself out there." (5739)

While many reports focused on describing musical progression, several also discussed progression to other kinds of activity. Mentions of continuing music/arts education in formal institutions such as colleges and universities were frequent:

15 of the participants have stated they will be enrolling onto music and arts courses at college come September. (5948)

Local colleges have held open days and our participants have attended, we have had the local college lecturers attend our sessions and had workshops with them telling them about music courses and other opportunities at the colleges… We have had participants attending open days and then applying to study at The Liverpool Institute for Performing Arts. Others have gone on to attend university in other parts of the country to study Music Management and Music Production. (6477)

Several other reports discussed the various employment opportunities participants had progressed to. For some, these were directly related to music:

We have attended open days held at Ad Lib (the leading provider of audio-visual training and suppliers of equipment to all of the major venues and festivals as well as world famous touring artists). Some of our young people have applied for work experience with them and hope to be starting in the next year. (6477)

One participant went on to work in paid capacity at Liverpool International Music Festival with tech operations staff. (6612)

Other employment opportunities mentioned were not music-related, or were not specified:

We have also signposted many to DCLT, who offer volunteer or employment opportunities for young people. (6851)

Legoland - full and part time employment - many of the young people have gained work at the park in various departments. (5883)

Alongside employment or work experience with specific organisations, there was also mention of training opportunities offered through the project which would put participants in good stead for accessing external employment opportunities in the future:

Some participants were able to access training in using DJ equipment, iPads and film-making through the programme. (6718)

Others have been signposted to training opportunities (in one case, acting classes). (5739)

There were many instances of how participation in a Youth Music project led to engaging or re-engaging with school, college, and further training:

Seven young people who had not thought of going to college before the project have now applied. Two have already started. (6440)

Aspiration levels were taken on the basis of whether a participant wanted to pursue further education or training (and did not specifically have to be in music covered in the workshops). 43 [out of] 65 young people maintained or increased their aspiration levels throughout the programme, claiming that they still wanted to, or now were showing interest in further education or training. (6701)

The self-assessment questionnaires [completed by young people] at the start and end of the course as well as their weekly diaries is also strong evidence to support [their interest in further training].

"We can confirm that 6 students from [project] are now in further training with us" - Halton College. (6481)

Social outcomes

The inherently social nature of music-making can lead to a number of social outcomes including feelings of belonging, bonding with like-minded people and making/sustaining friendships, as well as more measurable outcomes such as speech and language development, engagement with the community and external services, and improving behavioural issues.

Many projects reported seeing their participants interacting with one another using music. This was particularly evident (but not exclusively) in projects with parents and babies/toddlers where it was seen to be “a great bonding experience with our own children too, practicing the songs together at home […] with the whole family joining in too” (5913). There were also many reports of participants forming friendships with other members of the group, finding common ground with people they may not have otherwise met. This often led to a stronger sense of belonging, which is particularly important when thinking about the barriers that many participants of Youth Music funded projects face:

"When we come together, we meet friends, we meet one another and feel we can talk... Because, for me, when I sing these songs make me feel happy.”

"Different friends, different characters, beauty of voice, use your talent, see lovely faces, feel lively again" (5723)

Music was described as helping to overcome barriers between people:

Yes, it’s like sport … you know in this place you can find cultural barriers, language barriers, even religious barriers but with music you just put that to the side and go through because everyone wants to learn an instrument, well I mean a lot of people want it. (6329)

There were also many instances of participants learning and developing confidence to use interpersonal and social skills, sometimes explicitly facilitated by the process of making music together:

“Students have learnt to take turns, to listen to each other and to share ideas without the worry of being laughed at or dismissed. Their self-esteem and confidence has increased”. (5291)

As part of their pupil case studies, teachers were asked to comment on changes in their pupils’ communication, focus, listening and team-work skills. The majority of teachers saw development in these skills, with comments including:

“To see how far my children’s focus, turn-taking and experimentation with music has come has been a brilliant experience.”

“Listening – this is something they struggle with in all lessons. But they were able to listen as identified in the first listening improvisation. The idea of waiting before making a sound to assess what is going on.”

“She can often lose focus when in group situations due to her disabilities, and can get too excited, but she remained calm and focused throughout the project and concert which was fantastic.” (5951, Teacher comments on pupil development)

Several projects talked about the ways in which their projects had helped participants with the development of their speech and language. This is often seen in early years projects looking at speech and language development in infants, but there were also instances of projects working with older participants, for whom English was an additional language:

“This is really helping their English language skills and communication as most participants are Czech or Slovakian. Confidence and self-esteem is improving with all participants” (6358)

"I just come here, no speak nothing English... Now, me speak and understand a little bit"

"I improve more my English because before I had scared to speak English, now I don’t have scared anymore" (5723)

There were also instances of significant improvement throughout the course of a project with those who had antisocial behavioural issues or difficulty integrating into groups:

At the time of writing the report none of the [Youth Offending Service] officers supervising our participants have amended their risk assessment on our participants. However, we are happy to report that there have been no arrests or convictions of any of our participants in 2018. In addition to this our staff members have been able to disrupt a number of conflicts that our participants have been involved in personally with people outside of our working group via pro-social modelling and education in conflict resolution and self-management. In post-programme interview records suggest that young people feel empowered as a result of what they have learned and have less fear around their ability to avoid conflict and their safety on the streets. (6498)

Social community

As well as change on an individual level, there are many ways in which social changes can happen on a group scale as a result of music-making. We have seen several projects reporting outcomes happening on a communal/community level as well.

Several reports talked about how a community of musicians and young people has been created within the project. Often this revolved around spending time together as a group outside of the direct music element to a project. Other times, this was due to the interactive and communicative element of music making it easier to bond people together:

Participants developed a strong sense of community. 85% of participants strongly agreed/agreed that they 'felt part of a community at Group A' by March 2019. (6594)

Communities could be built for everyone involved in a project: for example, this hospital project created a community not only with patients and music leaders, but also with hospital staff.

It takes time and patience for trust and understanding to build between us, as visitors, and the various members of the healthcare team. From reflecting on this evidence, we see that the addition of live music on a regular basis has facilitated community connectedness. A live interactive musical offer naturally enables boundaries to be broken down, creating a level playing-field for all involved, transforming spaces and those people within, changing moods and lifting spirits subtly. (5741)

There were many instances of young musicians engaging with their external communities. Much of the time this involved performing to members of the general public, often leading to positive feedback from audience members and in some cases, challenging communities’ negative stereotypes of young people:

An audience members at the live event said " there wasn't one bad track in that performance, I'm going to buy the album" another said "were all these musicians before they started?" and when the reply was " No, for some of them it was the first time they have ever performed. " they had a look of disbelief. They all definitely improved their musical skills. (6877)

The perception of the young people still remains a difficult one to change, as many people within the community see the negative press stories and news reports and this influences their thoughts and creates stereotypes. Our good work has been observed by many in the community, but there are still some who hold the belief that young people are 'hoodlums'. (6090)

There was also a theme around participants of a group accessing different services in the community. For some participants, the project in question was the only service that they were engaging with. But a good experience can increase participants’ confidence to try something else, and in several instances, participants ended up connecting with other organisations and services for further support.

Identifying [project] groups as a city-wide initiative to access families was also very successful. They are well attended, and families often become regulars for months rather than weeks. It became apparent that many of these families don’t visit other groups or services as they don’t feel safe outside this bilingual, refugee and migrant setting. Given the current climate around issues of migration, using music as a means to create more united communities seems especially important.

“When we make music as a group it unites us all regardless of background and nationality.” Parent (6155)

L discussed some worries he is having about the state of the world and its effect on his mental health. He still appears optimistic but is clearly troubled by some thought he is having. Seems outwardly cheery but is obviously struggling internally. […] L discussed his mental health issues and talked about the positive steps he has made to get some more support with this. L has been to see his new GP and expressed relief in meeting him as he was very supportive […] L shows signs he is feeling positive about getting some support with his mental health but is still struggling. I now feel that he is more comfortable being honest about how he feels and that we have more trust between us. (6374)

Workforce outcomes

Alongside the wide variety of outcomes for children and young people taking part in Youth Music funded projects, there were also many outcomes reported for the workforce supporting them. Youth Music projects often contain an element of continuing professional development (CPD) for the workforce. Particularly in larger, more strategic grants, this is high on the list of priorities and can be hugely beneficial - not only for individual staff members, but for the organisations seeking to embed musically inclusive practice.

Organisations submitting evaluation reports in 2019/20 reported that over the course of their programmes of work:

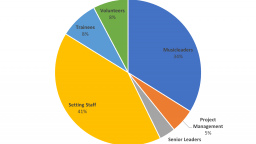

- 4,430 people were involved in delivering music making activities at projects funded by Youth Music.

- 3,583 people accessed continual professional development (CPD) opportunities as a result of Youth Music investment.

- There was a notable increase in the proportion of setting staff involved in delivering music-making activities from 26% in 2018/19, to 41% in 2019/20.

Commonly-reported themes were that the workforce supporting the participants on the Youth Music projects were learning and developing knowledge and skills, and/or becoming more confident in their roles as a result of being able to share ideas with peers. Often, this was as a result of attending specific training or practice-sharing events developed by the reporting project, or an external partner.

In order to ensure supportive and inclusive environments for young people facing barriers to music-making, many Youth Music funded organisations operate their projects in partnership with different agencies (e.g. specialist settings such as Pupil Referral Units) or through employing specialist staff members on the project (e.g. youth support workers providing pastoral support alongside the musical development). This means that there were many reports of workforce members from different disciplines sharing practice and gaining knowledge about working in different ways as a result of working together on the projects. There were reports of musicians and music leaders learning more about specific ways of working with different target groups, or having to think in a more inclusive way than they were used to:

Training and CPD has been a key aim for 2018/19. [Project] musicians each attended over 12 hours of training with respiratory physiotherapists to improve clinical understanding of conditions such as cystic fibrosis and asthma. This has impacted upon the musicians’ practice with young people, designing music activities that support breath management through both singing and beatboxing. It has also influenced evaluation practices, placing emphasis on reflective journaling to further enable artists in critically appraising methods of creatively engaging young people whilst supporting physical health. (6471)

There were also instances of non-music specialist staff in partner/referral settings (such as schools, nurseries, youth centres and hospitals) learning how to incorporate music into their work when music specialists were not around:

The project has had a transformative impact on the skills of the individual [Early Years Foundation Stage] practitioners who attended the training and then received additional support from us during the project. After more than 24 months of the project 88% of the practitioners reported using the Songo songs and activities with their children once a week or more. (5913)

In terms of supporting future generations of the workforce, there were many reports of mentoring and trainee programmes, often involving older or ex-participants of a particular project who aspired to progress and become music leaders themselves:

Louis originally joined [project 1] as a young person, progressed to being employed as a support worker, then joined [project 2] as a music leader. Working in partnership with Adam at the PRU and Benfield School has helped him build on his skills from Phase 2 and develop confidence. He has become a much-respected member of the team and was a particular support to the project during the period of [organisation’s] closure. (6358)

Workforce motivation and satisfaction

Alongside the skills and knowledge developed, there were also several themes relating to the workforce’s motivation and job satisfaction.

For many, this was a result of having a supportive and safe working and training environment, with a judgement-free opportunity to air concerns, ask questions and learn new things. There were also several instances of workforce members reporting increased confidence in their roles as musicians:

One of the [project] tutors who worked with us throughout the project - Alistair - has already been back to the Avenue school to deliver a series of workshops with the students there, which the [project] lead reports is a direct result of Alistair's increased confidence and enthusiasm for working with young people with SEND. (6752)

Finally, specific to music projects taking place in hospitals, there were a few reports that having music on the wards is cheering for hospital staff, for whom long, tiring and stressful days are often the norm, but also that it can be helpful for them when trying to calm patients down or distract them during a procedure, suggesting it can make hospital staff’s jobs easier at times:

Medical student report: Mr K, a consultant paediatrician, finds [project’s] practice “transformative – [they] change a place that may be hostile into a welcoming, creative space. It’s quite powerful.” A long-time member of the department, he was well-acquainted with [project] and had put some thought into why they have the effect they have: “[project’s] live music provides a deflection from an entirely clinical picture that may otherwise consume the parents and child back to the personal relationship between them. It’s a kind of unique magic that cuts through the discomfort of the child.” On a professional level, he says that [project] “creates a pleasant working environment that persists long after they have left.”

11/1/18 - Feedback card: 'Really look forward to working Fridays... [Musicians] provide calmness to what can be a really stressful job... watching parents sit and look at their babies; such a beautiful moment – Nurse (5741)

Organisational outcomes

As well as benefits for members of the workforce on an individual level, Youth Music projects reported on a number of outcomes for their wider organisation, and the music education sector as a whole. Youth Music’s vision is for a musically inclusive England, and there were several ways in which organisations were using Youth Music funding to gain more knowledge on topics around inclusion, partner with each other in order to share this knowledge and to develop progression pathways for young people, and to fully embed this learning into their daily practices.

Many organisations discussed developing tools and resources on particular topics and sharing these with others, or in one case, creating and hosting an online network for practitioners. Others described how they had developed responsive and user-centred training for members of their own and other organisations’ workforce:

We hadn’t expected to attract such specialised music leaders with training skills – it was really successful working with them to develop the CPD programme, and to incorporate their skills into delivering 5 of the sessions. It has helped to establish our local network of practitioners and to showcase the pool of local talent to partners and providers. Our practitioners have also created a diverse set of resources. (6155)

Reflecting on our desire to offer a Level 1 Music qualification, we realised that the process by which practitioners develop their skills is typically much more organic than completing a specific course. Just as we have learned to validate ‘non-musical’ music making, we’ve also learned that musical development is an amorphous and individual process. Our experience from this project has led us to a realisation that music will not happen of its own accord; rather it needs to be constantly supported and led by interested individuals. Since the motivation is there to retain a focus on musicality and not lose it, there is a clear need to materially support this focus in the future. If we were to set out on this project now, we would redefine this goal as becoming a centre of musical ‘abundance’ rather than ‘excellence’. (6180)

Many organisations discussed how they shared their expertise, resources, and learning through presentations at All-Party Parliamentary Groups, conferences and events, and likewise learnt new things through speaking to and hearing from other organisations in the sector.

Developing resources and attending training, as well as sharing the learning from successful projects at national conferences, appears to have established a level of experience and expertise amongst a number of organisations. Several organisations reported using their reputation as musical inclusion experts to work with and influence other providers – including Music Education Hubs and local authorities – to think and work more inclusively. Aside from being able to influence external organisations to embed musically inclusive practice, organisations also reported on the other benefits to networking with partners. Several reports mentioned that networking with partner organisations had increased and improved musical progression routes for young people.

Summary

This article has explored some of the main themes coming out of Youth Music’s funded work and is just a small selection of quotes from reports submitted by grantholders this year. Evaluation reports submitted to Youth Music have demonstrated just how impactful the work is to young musicians and the workforce and organisations supporting them. Although young people and the music education sector have faced unprecedented challenges in 2020, music continues to be a powerful resource for many. Thank you to all the projects whose final evaluation reports are featured here, and to all the others in our portfolio.

“Drugs, drinking and stealing were always on the agenda... being beaten up and threatened with a knife... stealing cars and running drugs for the big boys... It was a downward spiral for my boy. The police were involved and social services.. then [Youth Offending Team]... THEN [PROJECT]. Thank you for giving me my kind beautiful son back. He works hard now as a well-respected labourer. The turn around is amazing I know most of it was his own work but my god [project] was there at just the right time in my boy’s life. Thank you for letting him live inside the music you create and letting his bars be his way of coping with life the right way!” (6440)