The Clarion - an accessible musical instrument 8 years in the making.

The Clarion is an accessible musical instrument 8 years in the making. A key componant of OpenUp Music's groundbreaking Open Orchestras programme, the Clarion can be played with any part of the body, including your head, feet or even your eyes. In this post, OpenUp Music's CEO and Technical Director Barry Farrimond shares the journey the organisation has been on over the past 8 years...

In 2007 I co-founded a Community Interest Company called the MUSE Project, an organisation that would re-launch in 2014 as OpenUp Music with our wonderful Musical Director Doug Bott. Back in 2007 I had just left Bath Spa University with a BA Hons in Creative Music Technology and was keen to put my newly honed skills to work. I had had an idea to create a multi-sensory musical device for young disabled people, and together with MUSE co-founder Dr Duncan Gillard (a leading Educational Psychologist from Bristol), we managed to scrape together the £1,892 pounds required to get to work.

The device resembled a large circular table, divided into quarters of red, blue, green and yellow, with each section covered in a different sensory material. The blue section was covered in fake fur (the kind you might use to make a muppet); yellow was coated in smooth Perspex; red with dappled anti-slip vinyl; and green coated in fake grass. Each section housed a different array of sensors; a distance sensor (located within a newly purchased and brightly coloured toilet u-bend) measured how far away a musicians hand might be; 5 pressure sensors acted as drum pads; a slide sensor shaped like an arrow detected a hand moving along its surface; and finally a rotary sensor was used to produce the sound of a record being scratched - we called our invention the MUSE Board.

We put our heart and souls into the creation of the MUSE Board, toiling away in the darkness of my basement for months before finally finishing it in late 2008. The end result was admittedly a little on the large size (we had to cut the table down the middle and add a piano hinge to enable it to be folded in half) but we were happy with the way it looked and sounded. Excitedly, we set up a trial at a local special school and, having transported the large device in my tiny Peugeot 206 (pure comedy), proceeded to get everything set up for a small group of young people who had been selected by the school to take part.

The first participant was a wheelchair user with cerebral palsy. He was notably excited by the appearance of the MUSE Board and made a beeline for the blue section. What happened next had the most profound influence on me, and ultimately set the direction of travel for our musical instrument development programme over the next 7 years. The young man was completely unable to get his legs under the MUSE Board. When we positioned his chair sideways to enable him to reach it, the sensors - built statically into the device - were completely unable to measure or adapt to his movements and he was unable to play in any meaningful way. After the session the feedback from teachers was...honest shall we say. The MUSE Board was completely unusable for most of their pupils, it was large, it was heavy, it was expensive, and it required a dedicated music technologist to set the thing up. It was useless and we were devastated.

Now, most organisations might be forgiven for keeping this type of thing quiet. Who after all would want to be associated with this type of failure? I'm telling you this because I believe passionately in sharing learning (most importantly the stuff that doesn't work) but also because failure, when it's done right, "is simply the opportunity to begin again, this time more intelligently” (Henry Ford). This failure was the most valuable learning experience of my career but I would be lying if I said we didn't feel like giving up. We had sunk hundreds of pounds of our own money, months of time and quite a few litres of blood, sweat and tears into the MUSE Board. But we didn't give up, instead, we embarked on a 7 year period of intensive research and development that would culminate in the creation of a musical instrument that is already transforming musical access for young disabled musicians across the country - the Clarion.

Before we get to that part I think that it would be worth outlining again what we had learned from that crucial first failure, and how we set about beginning again more intelligently. The lessons learned were very clear - the MUSE Board was too big; it was too expensive; it was too complex, and ultimately it was inaccessible to both teachers and young disabled people. Big. Expensive. Complex. Inaccessible. But the most valuable lesson? We had failed to consult a single young disabled person, teacher, parent, carer or external music leader in the creation of the MUSE Board. It was at this stage that we sought the help of esteemed Cardiff Metropolitan University academic Dr Wendy Keay-Bright.

Dr Keay-Bright had utilised a methodology called "participatory design" in the creation of some fantastic interactive software for children on the autistic spectrum - ReactTickles Magic and Somantics. Participatory design (originally co-operative design, now often co-design) is an approach to design that actively involves all stakeholders (e.g. young people, teachers, music leaders, parents) in the design process to help ensure the results meet their needs and are usable. It is a cyclical process - you create crude, rapid prototypes that are used immediately; user feedback is captured through a range of appropriate means; the feedback is analysed; the prototypes are redesigned, implemented; and then the cycle repeats again...and again...and again...

In 2012, with the support of Youth Music and in partnership with Cardiff Metropolitan University and CARIAD Interactive, we launched the far-reaching R&D programme "Listening Aloud". The programme gave rise to a wide range of prototype musical instruments, all developed through participatory design. Together we created prototypes based upon face tracking algorithms, eye-tracking, 3D motion capture, accelerometers, EOG sensors, EEG sensors, joysticks...the list goes on and on. But at all times we were guided by the feedback we had received at the very start of our journey, that these prototypes should avoid being big, expensive, complex and inaccessible.

Josh's Instrument from OpenUp Music on Vimeo.

Open Musical Instruments from OpenUp Music on Vimeo.

2012 was an incredible year for disabled-led music, many of you will remember the fantastic Paralympic closing ceremony where Coldplay were joined on stage by members of the British Paraorchestra. I remember the ripples of excitement spreading from classroom to classroom as pupils and staff watched the performance back on YouTube. It was within this climate of raised expectation and aspiration that I had a passing conversation with a member of staff from the school that would change everything. "It was fantastic wasn't it?" he beamed "What we need now is a school orchestra!" Boom. Mic dropped. We had been searching for a meaningful musical context within which our instrument prototypes could continue to be tried and tested by young disabled people, now we had one.

Research revealed a fairly bleak picture of orchestral provision within special schools. I made a lot of phone calls, contacting schools across the south-west of England to ask if they had a school orchestra. Just over 50% of the mainstream secondary schools told me that they had one - not a single special school did. To add insult to injury at least two of the receptionists I spoke to from those special schools actually laughed at the question, with one asking me if I was aware that their school was ‘special’. Unfortunately, there was nothing special about what I found out that morning. Across the UK there are very few orchestras within special schools and there appear to be even fewer youth ensembles outside of school that make provision for the young disabled musicians we work with (Youth Ensembles Survey Report 2014 - Association of British Orchestras.) It was this tragic paucity of provision, expectation and musical progression that led to the founding of OpenUp Music and the launch of our Open Orchestras programme in 2014.

Thanks to the feedback we had earned so painfully back in 2007 and the participatory design contributions of countless young people, teachers and music leaders ever since, we had a raft of accessible musical instrument prototypes to make this work possible. Our prototypes were affordable, employing off the shelf technology like the XBox Kinect, webcams and the shamefully underused SmartNav to afford access. They were small and modular, able to be combined in a multitude of different ways to best suit the requirements of the musician playing them. And they were expressive, affording our musicians the opportunity to have dynamic control over their musical instruments. One prototype even won the Concept Award in the 2016 OHMI Trust competition But they remained complex, still requiring the presence of a well trained music technologist to help set them up, and were wrought with software bugs that I had to wrestle with on a daily basis. For those reasons, for all its success, our first year pilot of Open Orchestras was not yet transferable. This film charts the journey we went on during that first year, including a section on the musical instrument prototypes we were using at the time - well worth a watch if you have 20 minutes to spare.

OpenUp Music from OpenUp Music on Vimeo.

The first Open Orchestras year was incredible, we had launched 3 of the UK's first special school orchestras, provided our budding young musicians with the opportunity to play live at the Bristol Colston Hall and founded an organisation that now specialised in empowering young disabled musicians to build inclusive youth orchestras. But despite these achievements, we knew that countless more young disabled people were not being given the opportunity to play in a school orchestra. Our aim was (and still is) clear, we wanted all special schools to have an orchestra and all young people to have the opportunity to take part. If we wanted to make that a reality, we had to ensure that the Open Orchestras model was transferable. And so in 2015, we approached Youth Music, the Nominet Trust and the Bristol Music Trust to ask for support to develop a fully realised accessible musical instrument. I had drawn up designs that unified the very best features of our prototypes - this would be an expressive, affordable and accessible musical instrument that was rock solid, easy to use and transferable.

The 'Clarion' - named after OpenUp Music’s Paton, the world-famous disabled musician Clarence Adoo MBE, and coded by the indomitable Paul Masri - is a challenging instrument to pigeonhole. In many respects, it isn’t a single musical instrument at all, but a near-infinite number of instruments all contained within a single piece of musical software. What makes the Clarion unique is that it allows the musician or music leader to easily alter every conceivable element of the instrument. This includes the sound the instrument makes; the number of notes that are available to play; the shape, position and colour of the notes; and crucially the way in which you play them. For whilst it is entirely possible to play the Clarion with your fingers - it is also possible to play it with any other part of the body, including your head, feet or even with your eyes. The crucial difference is that the instrument adapts to the musician, not the other way around. This short film tells the story of Bradley Warwick, a Clarion player from a groundbreaking orchestra we launched in September 2015 - the South-West Open Youth Orchestra, the UK's only disabled-led regional youth orchestra.

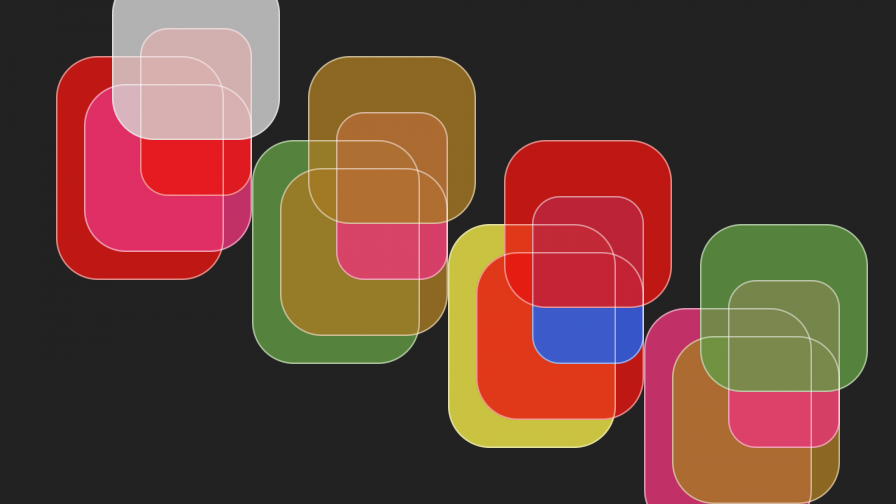

As previously mentioned, every conceivable element of the Clarion can be tweaked to ensure that it meets the needs of the musician. Notes are represented on its surface as shapes that can be coloured, resized, reformed and rotated. You can have one shape or hundreds and they can be moved anywhere on the surface, ensuring that they are positioned exactly where the musician requires them. The notes are also expressive, affording the player a range of different performance articulations that are affected by the speed of travel and your position within each shape. The pictures below illustrate just some of the myriad ways in which the Clarion's surface can be arranged.

Running on both iPad and Windows, and compatible with a wide range of off the shelf assistive technologies, the Clarion has proved crucial to the expansion of Open Orchestras. It is by no means the only instrument our musicians use, that would be boring, but it does ensure that some of the most marginalised young disabled musicians can have access to an expressive, affordable and accessible musical instrument. Sadly it is not yet on general release, but it is already ensuring that Open Orchestras is truly transferable. From September 2016, and in partnership with 6 music educations hubs and 16 schools, OpenUp Music is proud to announce the launch of 16 new Open Orchestras that stretch from Truro in the south-west to Tyneside in the north-east. Over 150 young disabled people will be taking part during the year and, thanks to the lessons learned over the past 8 years, we are moving ever closer to helping every special school in the country have it's very own orchestra.